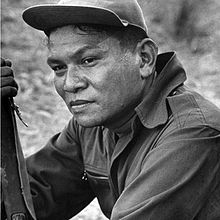

Ramon Magsaysay

Ramon Magsaysay | |

|---|---|

| |

| 7th President of the Philippines | |

| In office December 30, 1953 – March 17, 1957 | |

| Vice President | Carlos P. Garcia |

| Preceded by | Elpidio Quirino |

| Succeeded by | Carlos P. Garcia |

| 6th Secretary of National Defense | |

| In office January 1, 1954 – May 14, 1954 | |

| President | Himself |

| Preceded by | Oscar Castelo |

| Succeeded by | Sotero B. Cabahug |

| In office September 1, 1950 – February 28, 1953 | |

| President | Elpidio Quirino |

| Preceded by | Ruperto Kangleon |

| Succeeded by | Oscar Castelo |

| Member of the House of Representatives from Zambales’ Lone district | |

| In office May 28, 1946 – September 1, 1950 | |

| Preceded by | Valentin Afable |

| Succeeded by | Enrique Corpus |

| Military Governor of Zambales | |

| In office February 1, 1945 – March 6, 1945 | |

| Appointed by | Douglas MacArthur |

| Preceded by | Jose Corpuz |

| Succeeded by | Francisco Anonas |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ramon del Fierro Magsaysay August 31, 1907 Iba, Zambales, Philippines[a] |

| Died | March 17, 1957 (aged 49) Balamban, Cebu, Philippines |

| Cause of death | Airplane crash |

| Resting place | Manila North Cemetery, Santa Cruz, Manila, Philippines |

| Political party | Nacionalista (1953–1957) |

| Other political affiliations | Liberal (1946–1953)[1][2] |

| Spouse | |

| Children |

|

| Alma mater | University of the Philippines José Rizal University (BComm) |

| Profession | Soldier, automotive mechanic |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Philippine Commonwealth Army |

| Years of service | 1942–1945 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | 31st Infantry Division |

| Battles/wars | |

Ramon del Fierro Magsaysay Sr. QSC GCGH KGE GCC (August 31, 1907 – March 17, 1957) was a Filipino statesman who served as the seventh President of the Philippines, from December 30, 1953 until his death in an aircraft disaster on March 17, 1957. An automobile mechanic by profession, Magsaysay was appointed military governor of Zambales after his outstanding service as a guerrilla leader during the Pacific War. He then served two terms as Liberal Party congressman for Zambales's at-large district before being appointed Secretary of National Defense by President Elpidio Quirino. He was elected president under the banner of the Nacionalista Party. He was the youngest to be elected as president, and second youngest to be president (after Emilio Aguinaldo). He was the first Philippine president born in the 20th century and the first to be born after the Spanish colonial era.

Biography

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]

Ramon del Fierro Magsaysay, of mixed Tagalog, Visayan, Spanish, and Chinese descent, [3][4] was born in Iba, Zambales on August 31, 1907, to Exequiel de los Santos Magsaysay (April 18, 1874 in San Marcelino, Zambales – January 24, 1969 in Manila), a blacksmith, and Perfecta Quimson del Fierro (April 18, 1886 in Castillejos, Zambales – May 5, 1981 in Manila), a Chinese mestizo schoolteacher, nurse.[5][3]

He spent his grade school life somewhere in Castillejos and his high school life at Zambales Academy in San Narciso, Zambales.[6] After college, Magsaysay entered the University of the Philippines in 1927,[6] where he enrolled in a Mechanical Engineering course. He first worked as a chauffeur to support himself as he studied engineering; and later, he transferred to the Institute of Commerce at José Rizal College (now José Rizal University) from 1928 to 1932,[6] where he received a baccalaureate in commerce. He then worked as an automobile mechanic for a bus company[7] and shop superintendent.

Career during World War II

[edit]

At the outbreak of World War II, he joined the motor pool of the 31st Infantry Division of the Philippine Army.

When Bataan surrendered in 1942, Magsaysay escaped to the hills, narrowly evading Japanese arrest on at least four occasions. There he organised the Western Luzon Guerrilla Forces, and was commissioned captain on April 5, 1942. For three years, Magsaysay operated under Col. Frank Merrill's famed guerrilla outfit and saw action at Sawang, San Marcelino, Zambales, first as a supply officer codenamed Chow and later as commander of a 10,000-strong force.[5]

Magsaysay was among those instrumental in clearing the Zambales coast of the Japanese prior to the landing of American forces together with the Philippine Commonwealth troops on January 29, 1945.[citation needed]

Family

[edit]He was married to Luz Rosauro Banzon on June 16, 1933, and they had three children: Teresita (1934–1979), Milagros (b. 1936) and Ramon Jr. (b. 1938).

Other Relatives

Several of Magsaysay's relatives became prominent public figures in their own right:

- Ramon "Jun" Banzon Magsaysay Jr., son; former Congressman and Senator

- Francisco "Paco" Delgado Magsaysay, entrepreneur

- Genaro Magsaysay, brother; former Senator

- Vicente Magsaysay, nephew; Former Governor of Zambales

- JB Magsaysay, grandnephew; actor, politician, and businessman

- Antonio M. Diaz, nephew; Congressman and Assemblyman of Zambales

- Anita Magsaysay-Ho, cousin; painter

House of Representatives (1945–1950)

[edit]On April 22, 1946, Magsaysay, encouraged by his fellow ex-guerrillas, was elected under the Liberal Party[1] to the Philippine House of Representatives. In 1948, President Manuel Roxas chose Magsaysay to go to Washington, D.C. as Chairman of the Committee on Guerrilla Affairs, to help to secure passage of the Rogers Veterans Bill, giving benefits to Philippine veterans.[citation needed] In the so-called "dirty election" of 1949, he was re-elected to a second term in the House of Representatives. During both terms, he was Chairman of the House National Defense Committee.[citation needed]

Secretary of National Defense (1950–1953)

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2011) |

In early August 1950, he offered President Elpidio Quirino a plan to fight the Communist guerrillas, using his own experiences in guerrilla warfare during World War II. After some hesitation, Quirino realized that there was no alternative and appointed Magsaysay Secretary of National Defence in September 1950.[8] He intensified the campaign against the Hukbalahap guerrillas. This success was due in part to the unconventional methods he took up from a former advertising expert and CIA agent, Colonel Edward Lansdale. In the counterinsurgency the two utilized deployed soldiers distributing relief goods and other forms of aid to outlying, provincial communities. Prior to Magsaysay's appointment as Defense Secretary, rural citizens perceived the Philippine Army with apathy and distrust. However, Magsaysay's term enhanced the Army's image, earning them respect and admiration.[9]

In June 1952, Magsaysay made a goodwill tour to the United States and Mexico. He visited New York, Washington, D.C. (with a medical check-up at Walter Reed Hospital) and Mexico City, where he spoke at the Annual Convention of Lions International.

By 1953, President Quirino thought the threat of the Huks was under control and Secretary Magsaysay was becoming too weak. Magsaysay met with interference and obstruction from the President and his advisers, in fears they might be unseated at the next presidential election. Although Magsaysay had at that time no intention to run, he was urged from many sides and finally was convinced that the only way to continue his fight against communism, and for a government for the people, was to be elected president, ousting the corrupt administration that, in his opinion, had caused the rise of the communist guerrillas by bad administration. He resigned his post as defense secretary on February 28, 1953,[10] and became the presidential candidate of the Nacionalista Party,[11] disputing the nomination with Senator Camilo Osías at the Nacionalista national convention.

1951 Padilla incident

[edit]

When news reached Magsaysay that his political ally Moises Padilla was being tortured by men of provincial governor Rafael Lacson, he rushed to Negros Occidental, but was too late. He was then informed that Padilla's body was drenched in blood, pierced by fourteen bullets, and was positioned on a police bench in the town plaza.[12] Magsaysay himself carried Padilla's corpse with his bare hands and delivered it to the morgue, and the next day, news clips showed pictures of him doing so.[13] Magsaysay even used this event during his presidential campaign in 1953.

The trial against Lacson started in January 1952; Magsaysay and his men presented enough evidence to convict Lacson and his 26 men for murder.[12] In August 1954, Judge Eduardo Enríquez ruled the men were guilty and Lacson, his 25 men and three other mayors of Negros Occidental municipalities were condemned to the electric chair.[14]

Manila Railroad leadership

[edit]Magsaysay was also the general manager of the Manila Railroad Company between October and December 1951. His tenure later motivated him to modernize the rail operator's fleet after stepping into presidency. He also set the first steps in building what has been the discontinued Cagayan Valley Railroad Extension project.[15]

1953 presidential campaign

[edit]Presidential elections were held on November 10, 1953, in the Philippines. Incumbent President Elpidio Quirino lost his opportunity for a second full term as President of the Philippines to former Defense Secretary Magsaysay. His running mate, Senator José Yulo lost to Senator Carlos P. García. Vice President Fernando López did not run for re-election. This was the first time that an elected Philippine President did not come from the Senate. Moreover, Magsaysay began the practice in the Philippines of "campaign jingles" during elections, for one of his inclinations and hobbies was dancing. The jingles that were used during the election period was "Mambo Magsaysay"", "We Want Magsaysay", and "The Magsaysay Mambo"

The United States Government, including the Central Intelligence Agency, had strong influence on the 1953 election, and candidates in the election fiercely competed with each other for U.S. support.[16][17]

Presidency (1953–1957)

[edit]| Presidential styles of Ramon Magsaysay | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Excellency |

| Spoken style | Your Excellency |

| Alternative style | Mr. President |

In the election of 1953, Magsaysay was decisively elected president over the incumbent Elpidio Quirino. He was sworn into office on Wednesday, December 30, 1953, at the Independence Grandstand in Manila.[18] He was wearing the barong tagalog, a first by a Philippine President and a tradition that still continues up to this day. He was then called "Mambo Magsaysay". Also dressed in barong tagalog was the elected vice-president Carlos P. Garcia.[19] The oath of office was administered by Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines Ricardo Paras. For the first time, a Philippine president swore on the Bible on an inauguration.[20] He swore on two Bibles, from each parents' side.[21]

As President, he was a close friend and supporter of the United States and a vocal spokesman against communism during the Cold War. He led the foundation of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, also known as the Manila Pact of 1954, that aimed to defeat communist-Marxist movements in Southeast Asia, South Asia and the Southwestern Pacific.

During his term, he made Malacañang literally a "house of the people", opening its gates to the public. One example of his integrity followed a demonstration flight aboard a new plane belonging to the Philippine Air Force (PAF): President Magsaysay asked what the operating costs per hour were for that type of aircraft, then wrote a personal check to the PAF, covering the cost of his flight. He restored the people's trust in the military and in the government.

-

The taking of the oath of office of President Ramon Magsaysay

Administration and cabinet

[edit]Domestic policies

[edit]| Population | |

|---|---|

| 1954 | 21.40 million |

| Gross Domestic Product (1985 constant prices) | |

| 1954 | |

| 1956 | |

| Growth rate, 1954–56 | 7.2% |

| Per capita income (1985 constant prices) | |

| 1954 | |

| 1956 | |

| Total exports | |

| 1954 | |

| 1956 | |

| Exchange rates | |

| 1 US US$ = Php 2.00 1 Php = US US$ 0.50 | |

| Sources: Philippine Presidency Project Malaya, Jonathan; Eduardo Malaya. So Help Us God... The Inaugurals of the Presidents of the Philippines. Anvil Publishing, Inc. | |

Presidential Inauguration Day

[edit]Ushering a new era in Philippine government, President Magsaysay placed emphasis upon service to the people by bringing the government closer to the former.[2]

This was symbolically seen when, on inauguration day, President Magsaysay ordered the gates of Malacañan Palace be opened to the general public, who were allowed to freely visit all parts of the Palace complex. Later, this was regulated to allow weekly visitation.[2]

True to his electoral promise, he created the Presidential Complaints and Action Committee.[2] This body immediately proceeded to hear grievances and recommend remedial action. Headed by soft-spoken, but active and tireless, Manuel Manahan, this committee would come to hear nearly 60,000 complaints in a year, of which more than 30,000 would be settled by direct action and a little more than 25,000 would be referred to government agencies for appropriate follow-up. This new entity, composed of youthful personnel, all loyal to the President, proved to be a highly successful morale booster restoring the people's confidence in their own government. He appointed Zotico "Tex" Paderanga Carrillo in 1953 as PCAC Chief for Mindanao and Sulu. He became a close friend to the president because of his charisma to the common people of Mindanao.[citation needed]

Zotico was a local journalist and a writer from a family on Camiguin, (then sub-province of Misamis Oriental), Zotico become a depository of complaints and an eye of the president in the region his diplomatic skills helped the government, moro and the rebels to learn the true situation in every city and municipalities. With his zero corruption mandate he recognized a turn of achievement of Zotico that made him his compadre when Zotico named his fifth child after the President when he was elected in 1953, even making the President godfather to the boy. Magsaysay personally visited Mindanao several times because of this friendship, becoming the first President to visit Camiguin, where he was warmly received by thousands of people who waited for his arrival.[2]

Agrarian reform

[edit]To amplify and stabilize the functions of the Economic Development Corps (EDCOR), President Magsaysay worked[2] for the establishment of the National Resettlement and Rehabilitation Administration (NARRA).[2] This body took over from the EDCOR and helped in the giving some sixty-five thousand acres to three thousand indigent families for settlement purposes.[2] Again, it allocated some other twenty-five thousand to a little more than one thousand five hundred landless families, who subsequently became farmers.[2]

As further aid to the rural people,[2] the president established the Agricultural Credit and Cooperative Financing Administration (ACCFA). The idea was for this entity to make available rural credits. Records show that it did grant, in this wise, almost ten million dollars. This administration body next devoted its attention to cooperative marketing.[2]

Along this line of help to the rural areas, President Magsaysay initiated in all earnestness the artesian wells campaign. A group-movement known as the Liberty Wells Association was formed and in record time managed to raise a considerable sum for the construction of as many artesian wells as possible. The socio-economic value of the same could not be gainsaid and the people were profuse in their gratitude.[2]

Finally, vast irrigation projects, as well as enhancement of the Ambuklao Power plant and other similar ones, went a long way towards bringing to reality the rural improvement program advocated by President Magsaysay.[2]

President Magsaysay enacted the following laws as part of his Agrarian Reform Program:

- Republic Act No. 1160 of 1954 – Abolished the LASEDECO and established the National Resettlement and Rehabilitation Administration (NARRA) to resettle dissidents and landless farmers. It was particularly aimed at rebel returnees providing home lots and farmlands in Palawan and Mindanao.

- Republic Act No. 1199 (Agricultural Tenancy Act of 1954) – governed the relationship between landowners and tenant farmers by organizing share-tenancy and leasehold system. The law provided the security of tenure of tenants. It also created the Court of Agrarian Relations.

- Republic Act No. 1400 (Land Reform Act of 1955) – Created the Land Tenure Administration (LTA) which was responsible for the acquisition and distribution of large tenanted rice and corn lands over 200 hectares for individuals and 600 hectares for corporations.

- Republic Act No. 821 (Creation of Agricultural Credit Cooperative Financing Administration) – Provided small farmers and share tenants loans with low interest rates of six to eight percent.[22]

Hukbong Bayan Laban sa Hapon

[edit]In early 1954, Benigno Aquino Jr. was appointed by President Magsaysay to act as his personal emissary to Luis Taruc, leader of the rebel group, Hukbalahap. Also in 1954, Lt. Col. Laureño Maraña, the former head of Force X of the 16th PC Company, assumed command of the 7th BCT, which had become one of the most mobile striking forces of the Philippine ground forces against the Huks, from Colonel Valeriano. Force X employed psychological warfare through combat intelligence and infiltration that relied on secrecy in planning, training, and execution of attack. The lessons learned from Force X and Nenita were combined in the 7th BCT.

With the all out anti-dissidence campaigns against the Huks, they numbered less than 2,000 by 1954 and without the protection and support of local supporters, active Huk resistance no longer presented a serious threat to Philippine security. From February to mid-September 1954, the largest anti-Huk operation, "Operation Thunder-Lightning" was conducted that resulted in Taruc's surrender on May 17. Further cleanup operations of the remaining guerrillas lasted throughout 1955, cutting their number to less than 1,000 by year's end.[23][24]

Foreign policies

[edit]

Southeast Asia Treaty Organization

[edit]The administration of President Magsaysay was active in the fight against the expansion of communism in Asia. He made the Philippines a member of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), which was established in Manila on September 8, 1954, during the "Manila Conference".[25] Members of SEATO were alarmed at the possible victory of North Vietnam over South Vietnam, which could spread communist ideology to other countries in the region. The possibility that a communist state can influence or cause other countries to adopt the same system of government is called the domino theory.[26]

The active coordination of the Magsaysay administration with the Japanese government led to the Reparation Agreement. This was an agreement between the two countries, obligating the Japanese government to pay $550 million as reparation for war damages to the Philippines.[26]

The SEATO agreement have proved to be unpopular among the Philippines' Asian neighbors, having its original members were the U.S., France, the U.K., Australia, Pakistan and New Zealand, with the U.S. as its driving force. His support for South Vietnamese president Ngo Dinh Diem became unpopular to the Vietnamese public especially those in the north. Magsaysay also pressured Cambodian Prince Norodom Sihanouk for Cambodia to join SEATO and claimed that the prince was violating Cambodia's non-alignment policy.[27]: 7-10

Defense Council

[edit]Taking the advantage of the presence of U.S. Secretary John Foster Dulles in Manila to attend the SEATO Conference, the Philippine government took steps to broach with him the establishment of a Joint Defense Council. Vice-President and Secretary of Foreign Affairs Carlos P. Garcia held the opportune conversations with Secretary Dulles for this purpose. Agreement was reached thereon and the first meeting of the Joint United States–Philippines Defense Council was held in Manila following the end of the Manila Conference. Thus were the terms of the Mutual Defense Pact between the Philippines and the United States duly implemented.[2]

Laurel-Langley Agreement

[edit]

The Magsaysay administration negotiated the Laurel-Langley Agreement which was a trade agreement between the Philippines and the United States which was signed in 1955 and expired in 1974. Although it proved deficient, the final agreement satisfied nearly all of the diverse Filipino economic interests. While some have seen the Laurel-Langley agreement as a continuation of the 1946 trade act, Jose P. Laurel and other Philippine leaders recognized that the agreement substantially gave the country greater freedom to industrialize while continuing to receive privileged access to US markets.[28]

The agreement replaced the unpopular Bell Trade Act, which tied the economy of the Philippines to that of United States.

Bandung Conference

[edit]The culmination of a series of meetings to promote Afro-Asian economic and cultural cooperation and to oppose colonialism or neocolonialism by either the United States or the Soviet Union in the Cold War, or any other imperialistic nations, the Asian–African Conference was held in Bandung, Indonesia in April 1955, upon invitation extended by the Prime Ministers of India, Pakistan, Burma, Ceylon, and Indonesia. This summit is commonly known as the Bandung Conference. Although, at first, the Magsaysay Government seemed reluctant to send any delegation. Later, however, upon advise of Ambassador Carlos P. Rómulo, it was decided to have the Philippines participate in the conference. Rómulo was asked to head the Philippine delegation.[2] At the very outset indications were to the effect that the conference would promote the cause of neutralism as a third position in the current Cold War between the capitalist bloc and the communist group. John Kotelawala, Prime Minister of Ceylon, however, broke the ice against neutralism.[2] He was immediately joined by Rómulo, who categorically stated that his delegation believed that "a puppet is a puppet",[2] no matter whether under a Western Power or an Asian state.[2]

In the course of the conference, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru acidly spoke against the SEATO. Ambassador Rómulo delivered a stinging, eloquent retort that prompted Prime Minister Nehru to publicly apologize to the Philippine delegation.[2] According to their account, the Philippine delegation ably represented the interests of the Philippines and, in the ultimate analysis, succeeded in turning the Bandung Conference into a victory against the plans of its socialist and neutralist delegates.[2] However according to the final communique of the conference, communism as a threat in Asia was not mentioned. Instead, participating countries viewed that colonialism, racialism, cultural suppression, discrimination, and nuclear weapons as regional threats. Solutions offered by the conference for these threats were less ideological, which namely includes:[27]: 8

(1) respect for human rights; (2) respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity of all nations; (3) recognition of the equality of all races and of all nations; (4) non-interference in the internal affairs of another country; (5) respect for the right of each nation to defend itself singly or collectively, in accordance with the UN Charter; (6) refraining from acts of threats or aggression or the use of force against another country; (7) promotion of mutual interests and cooperation; and (8) respect for justice and international obligations.

Reparation agreement

[edit]Following the reservations made by Ambassador Rómulo, on the Philippines' behalf, upon signing the Japanese Peace Treaty in San Francisco on September 8, 1951, for several years of series of negotiations were conducted by the Philippine government and that of Japan. In the face of adamant claims of the Japanese government that it found impossible to meet the demand for the payment of eight billion dollars by the way of reparations, President Magsaysay, during a so-called "cooling off"[2] period, sent a Philippine Reparations Survey Committee, headed by Finance Secretary Jaime Hernandez, to Japan for an "on the spot" study of that country's possibilities.[2]

When the Committee reported that Japan was in a position to pay, Ambassador Felino Neri, appointed chief negotiator, went to Tokyo. On May 31, 1955, Ambassador Neri reached a compromise agreement with Japanese Minister Takazaki, the main terms of which consisted in the following: The Japanese government would pay eight hundred million dollars as reparations. Payment was to be made in this wise: Twenty million dollars would be paid in cash in Philippine currency; thirty million dollars, in services; five million dollars, in capital goods; and two hundred and fifty million dollars, in long-term industrial loans.[2]

On August 12, 1955, President Magsaysay informed the Japanese government, through Prime Minister Ichiro Hatoyama, that the Philippines accepted the Neri-Takazaki agreement.[2] In view of political developments in Japan, the Japanese Prime Minister could only inform the Philippine government of the Japanese acceptance of said agreement on March 15, 1956. The official Reparations agreement between the two government was finally signed at Malacañang Palace on May 9, 1956, thus bringing to a rather satisfactory conclusion this long drawn controversy between the two countries.[2]

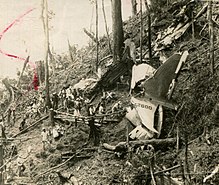

Death

[edit]Magsaysay's term, which was to end on December 30, 1957, was cut short by a plane crash. On March 16, 1957, Magsaysay left Manila for Cebu City where he spoke at a convention of USAFFE veterans and the commencement exercises of three educational institutions, namely: University of the Visayas, Southwestern Colleges, and the University of San Carlos.[29] At the University of the Visayas, he was conferred an honorary Doctor of Laws. That same night, at about 1:00 am PST, he boarded the presidential plane "Mt. Pinatubo", a C-47, heading back to Manila. In the early morning hours of March 17, the plane was reported missing. By late afternoon, newspapers had reported the airplane had crashed on Mount Manunggal in Cebu, and that 36 of the 56 aboard were killed. The actual number on board was 25, including Magsaysay. He was only 49. Only newspaperman Nestor Mata survived. Vice President Carlos P. Garcia, who was on an official visit to Australia at the time, returned to Manila and acceded to the presidency to serve out the remaining eight months of Magsaysay's term.[30]

|

|

|

An estimated two million people attended Magsaysay's state funeral on March 22, 1957.[31][32][33] He was posthumously referred to as the "Champion of the Masses" and "Defender of Democracy". After his death, vice-president Carlos P. Garcia was inducted into the presidency on March 18, 1957, to complete the last eight months of Magsaysay's term. In the presidential elections of 1957, Garcia won his four-year term as president, but his running mate was defeated.[34]

Legacy

[edit]

Magsaysay's administration was considered as one of the cleanest and most corruption-free in modern Philippine history; his rule is often cited as the Philippines's "Golden Years". Trade and industry flourished, the Philippine military was at its prime, and the country gained international recognition in sports, culture, and foreign affairs. The Philippines placed second on a ranking of Asia's clean and well-governed countries.[35][36]

His presidency is seen as people-centered as government trust was high among the Filipino people, earning him the nickname "Champion of the masses" and his sympathetic approach to the Hukbalahap rebellion that the Huk rebels were not Communists; they were simple peasants who thought that rebellion was the only answer to their sufferings. He also gained nationwide support for his agrarian reforms on farmers and took action on government corruption that his administration inherited from prior administrations.[37][38]

Honors

[edit]National Honors

: Quezon Service Cross - posthumous (July 4, 1957)[39]

: Quezon Service Cross - posthumous (July 4, 1957)[39] : Order of the Golden Heart, Grand Collar (Maringal na Kuwintas) - posthumous (March 17, 1958)[40] [41]

: Order of the Golden Heart, Grand Collar (Maringal na Kuwintas) - posthumous (March 17, 1958)[40] [41]

Military Medals (Foreign)

United States:

United States: : Commander, Legion of Merit (13 June 1952)

: Commander, Legion of Merit (13 June 1952)

Foreign Honors

Thailand: Knight Grand Cordon(Special Class) of The Most Exalted Order of the White Elephant (April 1955)[42]

Thailand: Knight Grand Cordon(Special Class) of The Most Exalted Order of the White Elephant (April 1955)[42] Cambodia: Grand Cross of the Royal Order of Cambodia (January 1956)[43]

Cambodia: Grand Cross of the Royal Order of Cambodia (January 1956)[43]

Ancestry

[edit]| Ancestors of Ramon Magsaysay | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The Philippines was a unincorporated territory of the United States known as the Philippine Islands at the time of Magsaysay's birth.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Ramon Magsaysay." Microsoft Student 2009 [DVD]. Redmond, WA: Microsoft Corporation, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Molina, Antonio. The Philippines: Through the centuries. Manila: University of Santo Tomas Cooperative, 1961. Print.

- ^ a b Tan, Antonio S. (1986). "The Chinese Mestizos and the Formation of the Filipino Nationality". Archipel. 32: 141–162. doi:10.3406/arch.1986.2316 – via Persée.

- ^ Ryan, Allyn C. (2007). A Biographical Novel of Ramon Magsaysay. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1-4257-9161-2.

- ^ a b Manahan, Manuel P. (1987). Reader's Digest November 1987 issue: Biographical Tribute to Ramon Magsaysay. pp. 17–23.

- ^ a b c House of Representatives (1950). Official Directory. Bureau of Printing. p. 167. Retrieved May 3, 2022.

- ^ Greenberg, Lawrence M. (1987). The Hukbalahap Insurrection: A Case Study of a Successful Anti-insurgency Operation in the Philippines, 1946-1955. Analysis Branch, U.S. Army Center of Military History. p. 79. Retrieved May 3, 2022.

- ^ Thompson, Roger C. (September 25, 2014). The Pacific Basin since 1945: An International History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-87529-1. Retrieved May 3, 2022.

- ^ Ladwig III, Walter C. (2014). When the Police are the Problem: The Philippine Constabulary and the Huk Rebellion (PDF). in C. Christine Fair and Sumit Ganguly, (eds.) Policing Insurgencies: Cops as Counterinsurgents. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 13, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ^ Barrens, Clarence G. (1970). I Promise: Magsaysay's Unique PSYOP "defeats" HUKS. US Army Command and General Staff College. p. 58. Retrieved May 3, 2022.

- ^ Simbulan, Dante C. (2005). The Modern Principalia: The Historical Evolution of the Philippine Ruling Oligarchy. UP Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-971-542-496-7.

- ^ a b "The Philippines: Justice for the Governor". Time Magazine. September 6, 1954. Archived from the original on November 28, 2009. Retrieved February 3, 2010.

- ^ "Remembering President Ramón Magsaysay y Del Fierro: A Modern-Day Moses". Retrieved February 3, 2010. A privileged speech by Senator Nene Pimentel delivered at the Senate, August 2001.

- ^ "The Philippines: Justice for the Governor". Time. September 6, 1954. Archived from the original on November 28, 2009. Retrieved February 3, 2010. Second page of Time's coverage of Rafael Lacson's case.

- ^ Satre, Gary (December 1999). "The Cagayan Valley Railway Extension Project". East Japan Railway Culture Foundation. Retrieved May 3, 2022.

- ^ Cullather, Nick (1994). Illusions of influence: the political economy of United States-Philippines relations, 1942–1960. Stanford University Press. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-8047-2280-3.

- ^ Tharoor, Ishaan (October 13, 2016). "The long history of the U.S. interfering with elections elsewhere". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 546121, 2019.

- ^ Inaugural Address of President Magsaysay, December 30, 1953 (Speech). Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. December 30, 1953. Retrieved June 2, 2023.

- ^ Halili, M.C. (2010). Philippine History. Rex Book Store, Inc.

- ^ Baclig, Cristina Eloisa (June 21, 2022). "Presidential inaugurations: Traditions, rituals, trivia". INQUIRER.net. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ Elefante, Fil (June 27, 2016). "Tales of past presidential inaugurations: Superstition and history". Business Mirror. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ "Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) – Organizational Chart". Archived from the original on February 18, 2010. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ Carlos P. Romulo and Marvin M. Gray, The Magsaysay Story (1956), is a full-length biography

- ^ Jeff Goodwin, No Other Way Out, Cambridge University Press, 2001, p.119, ISBN 0-521-62948-9, ISBN 978-0-521-62948-5

- ^ "Ramon Magsaysay – president of Philippines". August 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Grace Estela C. Mateo: Philippine Civilization – History and Government, 2006

- ^ a b Dagdag, Edgardo E. (1999). "The Philippines and the quest for stable peace in Southeast Asia: A historical overview" (PDF). Asian Studies.

- ^ Illusions of influence: the political economy of United States–Philippines. By Nick Cullather

- ^ Moneva, Dominico (March 18, 2006). "Speak out: Magsaysay's death". Sun Star Cebu. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ^ "Official Month in Review: March 16 – March 31, 1957". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. March 31, 1957. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ Zaide, Gregorio F. (1984). Philippine History and Government. National Bookstore Printing Press.

- ^ Townsend, William Cameron (1952). Biography of President Lázaro Cárdenas. See the SIL International Website at: Establishing the Work in Mexico.

- ^ Carlos P. Romulo and Marvin M. Gray: The Magsaysay Story (The John Day Company, 1956, updated – with an additional chapter on Magsaysay's death – re-edition by Pocket Books, Special Student Edition, SP-18, December 1957)

- ^ Halili, M.C. (2010). Philippine History. Rex Book Store, Inc.

- ^ Guzman, Sara Soliven De. "Has the government become our enemy?". Philstar.com. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ^ "Reforming the AFP Magsaysay's". National Historical Commission of the Philippines. September 5, 2012. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ^ FilipiKnow (November 27, 2016). "6 Reasons Why Ramon Magsaysay Was The Best President Ever". FilipiKnow. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ^ "Philippine History: President Ramon F. Magsaysay: Champion of the masses". ph.news.yahoo.com. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ^ "History of the Quezon Service Cross". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- ^ "President's Month in Review: March 16 – March 31, 1958". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines.

- ^ "Roster of Recipients of Presidential Awards". Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ "Official Month in Review: April 1955". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. April 1, 1955. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

In the afternoon the President received the decoration of the Knight Grand Cordon of the Most Exalted Order of the White Elephant, the highest decoration conferred by the government of Thailand.

- ^ "Official Month in Review: February 1956". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. February 1, 1956. Archived from the original on August 25, 2020. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

The Prince presented the President with the Grand Croix de l'Ordre Royal du Cambodge, Cambodia's highest decoration for a foreign chief of state.

External links

[edit]- Ramon Magsaysay on the Presidential Museum and Library Archived May 14, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Ramon Magsaysay on the Official Gazette

- Stanley J. Rainka Papers Finding Aid, 1945–1946, AIS.2009.04, Archives Service Center, University of Pittsburgh. (Correspondence with Ramon Magsaysay)

- "Did the CIA use pop music to help elect president of the Philippines?" by Robert Tollast, The National News, Jan 21, 2022

- Ramon Magsaysay

- 1907 births

- 1957 deaths

- Burials at the Manila North Cemetery

- Candidates in the 1953 Philippine presidential election

- Filipino anti-communists

- 20th-century Filipino engineers

- 20th-century Roman Catholics

- Filipino Roman Catholics

- Governors of Zambales

- Ilocano people

- José Rizal University alumni

- Magsaysay family

- Members of the House of Representatives of the Philippines from Zambales

- Nacionalista Party politicians

- Filipino paramilitary personnel

- People from Zambales

- Filipino people of Spanish descent

- Filipino people of Chinese descent

- Filipino people of Kapampangan descent

- Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Order of Cambodia

- Presidents of the Philippines

- People of the Cold War

- Quirino administration cabinet members

- Recipients of the Quezon Service Cross

- Secretaries of national defense of the Philippines

- State leaders killed in aviation accidents or incidents

- Tagalog people

- Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in 1957

- Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in the Philippines

- Filipino politicians of Chinese descent

- Filipino military personnel of World War II