Phantom of the Paradise

| Phantom of the Paradise | |

|---|---|

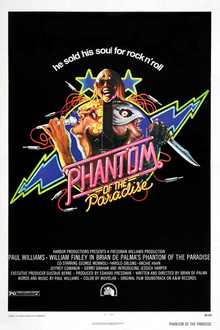

Theatrical release poster by John Alvin[1] | |

| Directed by | Brian De Palma |

| Written by | Brian De Palma |

| Produced by | Edward Pressman |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Larry Pizer |

| Edited by | Paul Hirsch |

| Music by | Paul Williams |

Production company | Harbor Productions |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 91 minutes[3] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.3 million |

Phantom of the Paradise is a 1974 American rock musical comedy horror film written and directed by Brian De Palma and scored by and starring Paul Williams.

A naïve young singer-songwriter, Winslow Leach (William Finley) is tricked by legendary but unscrupulous music producer Swan (Williams) into sacrificing his life's work. In revenge, the songwriter dons a menacing new persona and proceeds to terrorize Swan's new concert hall, insisting his music be performed by his most adored singer, Phoenix (Jessica Harper).

The plot loosely adapts several classic works: the 16th century Faust legend, Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray and Gaston Leroux's The Phantom of the Opera.[4]

The film was a box office failure and received mixed-to-negative reviews contemporaneously, while earning praise for its music and receiving Academy Award and Golden Globe nominations. However, over the years, the film has received much more positive reviews and has become a cult film.

Plot

[edit]Following a run-through by the 1950s-style nostalgia band the Juicy Fruits, star record producer Swan overhears singer-songwriter Winslow Leach perform an original composition: A song from the cantata based on the legend of Faust. Swan believes Winslow's music is ideal for the opening of The Paradise—Swan's highly anticipated new concert hall—and has his right-hand man Arnold Philbin steal it.

One month later, Winslow goes to Swan's Death Records headquarters to follow up about his music but is thrown out. He sneaks into Swan's private mansion, where auditions for singers are being held. There, he meets Phoenix, an aspiring singer Winslow deems perfect for his music. After repeated attempts to contact Swan, Winslow is beaten and framed for drug dealing and given a life sentence in Sing Sing prison. His teeth are extracted and replaced with metal ones.

Six months later, at Sing Sing, Winslow breaks down upon hearing of the Juicy Fruits' success and news that the band will open the Paradise performing Faust. He escapes prison in a delivery box and enters the Death Records building. A guard startles Winslow as he destroys the records and presses, causing him to slip and fall face-first into a record press, which burns the right half of his face and destroys his vocal cords. He escapes the studio and falls into the East River.

A disfigured Winslow sneaks into The Paradise's costume department and dons a black cape and silver, owl-like mask, transforming into the Phantom of the Paradise. He terrorizes Swan and his musicians, nearly killing the Beach Bums (formerly the Juicy Fruits, who have traded doo-wop for surf music) with a bomb while they play a reworked version of Winslow's Faust. The Phantom confronts Swan, who recognizes him as Winslow and offers him a chance to have his music produced his way. Swan provides Winslow with an electronic voice box, enabling him to speak and sing. Swan asks Winslow to rewrite his Faust cantata with Phoenix in mind for the lead. Although Winslow agrees and signs a blood contract, Swan breaks the deal. Winslow completes Faust, but Swan replaces Phoenix with a male glam rock prima donna named Beef.

Swan steals the completed cantata and seals Winslow inside the recording studio with a brick wall. He escapes and confronts Beef in the shower, threatening to kill Beef if he ever performs Winslow's music again. Beef tries to flee but is forced to perform. Winslow fatally electrocutes Beef with a stage prop from the wings. Horrified, Philbin orders Phoenix onstage, where her performance receives rapturous applause.

After the show, Swan promises Phoenix stardom. She is then confronted by Winslow, who implores her to leave The Paradise. However, Phoenix does not heed his warning. Winslow observes Swan and Phoenix in a tight embrace at Swan's mansion. Heartbroken, he stabs himself through the heart. Swan explains that Winslow cannot die until Swan himself has died. Winslow attempts to stab Swan, but he is unharmed, claiming he is "also under contract."

Rolling Stone announces the wedding between Swan and Phoenix during the finale of Faust. Winslow learns that Swan made a pact with the Devil in 1953: Swan will remain youthful forever, and the videotaped recording of his contract will age and fester in his place. The only way to break the spell is to destroy the video. Winslow realizes Swan is planning to have Phoenix assassinated during the ceremony. He destroys all the recordings and heads to the wedding.

During the wedding, Winslow stops the assassin from hitting Phoenix, with the bullet fatally wounding Philbin instead. Winslow swings onto the stage and rips off Swan's mask, exposing him as a decaying monster on live television. A crazed Swan attempts to strangle Phoenix, but Winslow intervenes and stabs him repeatedly, reopening his wound in the process. Swan dies, and Winslow soon follows. As Winslow dies, Phoenix finally recognizes and embraces him.

Cast

[edit]- Paul Williams as Swan / the Phantom's singing voice

- William Finley as Winslow Leach / the Phantom

- Archie Hahn, Jeffrey Comanor, and Harold Oblong as the Juicy Fruits / the Beach Bums / the Undeads

- George Memmoli as Arnold Philbin (named in tribute to Mary Philbin who starred as Christine in the 1925 film version of Phantom of the Opera)

- Gerrit Graham as Beef

- Raymond Louis Kennedy as Beef's singing voice

- Jessica Harper as Phoenix

- Mary Margaret Amato as Swan's groupie

- Janis Eve Lynn as a groupie

- Cheryl Smith as a groupie

- Rod Serling as the introductory voice (uncredited)

Musical numbers

[edit]The film's soundtrack album features all songs excluding "Never Thought I'd Get to Meet the Devil" and "Faust" (1st Reprise). All words and music are by Paul Williams.

- "Goodbye, Eddie, Goodbye" – The Juicy Fruits

- "Faust" – Winslow

- "Never Thought I'd Get to Meet the Devil" – Winslow

- "Faust" (1st Reprise) – Winslow, Phoenix

- "Upholstery" – The Beach Bums

- "Special to Me" – Phoenix

- "Faust" (2nd Reprise) – The Phantom

- "The Phantom's Theme (Beauty and the Beast)" – The Phantom

- "Somebody Super Like You" (Beef construction song) – The Undead

- "Life at Last" – Beef

- "Old Souls" – Phoenix

- "The Hell of It" (plays over end credits) – Swan

Charts

[edit]| Chart (1975) | Position |

|---|---|

| Australia (Kent Music Report)[5] | 94 |

Production

[edit]The root for making the film was a recollection that De Palma had hearing a Beatles song in an elevator played as "muzak" to go along with experiences trying to pitch material to indifferent executives and an idea from his friends (Mark Stone and John Weiser) about a "Phantom of the Fillmore". The script was written in tandem with Sisters (1972), although that film was done first because of its perceived commercial viability. Difficulty came with trying to get financing before real estate developer named Gustave Berne provided a majority of the funding; during the trips around studios trying to get funding, De Palma was introduced to Paul Williams, who had a handful of small roles on film but was mostly known for songwriting. While De Palma felt Williams was suited to play the character of Winslow, Williams felt he wasn't scary enough for the role and suggested playing Swan (once named Spectre in the script as a play on the famed producer Phil Spector) instead.[6]

The record press in which William Finley's character was disfigured was a real injection-molding press at Pressman Toys. He was worried about whether the machine would be safe, and the crew assured that it was. The press was fitted with foam pads (which resemble the casting molds in the press), and there were chocks put in the center to stop it from closing completely. Unfortunately, the machine was powerful enough to crush the chocks and it gradually kept closing. Finley was pulled out in time to avoid injury.

The electronic room in which Winslow composes his cantata, and where Swan restores his voice, is in fact the real-life recording studio The Record Plant. The walls covered with knobs are in reality an oversize custom-built electronic synthesizer dubbed TONTO.

The City Center concert hall in New York City provided the exterior for The Paradise; interior concert scenes were filmed at the Majestic Theater in Dallas, Texas. The extras in the audience had responded to an open cattle call for locals interested in being in the film.

Sissy Spacek was the film's set dresser, assisting Jack Fisk, the film's production designer, whom she would later marry. She later starred in De Palma's Carrie in 1976.[7]

The film was financed independently. Producer Pressman then screened the movie to studios and sold it to the highest bidder, 20th Century Fox, for $2 million plus a percentage.[8]

As originally filmed, the name of Swan's media conglomerate "Swan Song Enterprises" had to be deleted from the film prior to release due to the existence of Led Zeppelin's label Swan Song Records. Although most references were removed, "Swan Song" remains visible in several scenes.[9]

Release

[edit]Phantom of the Paradise opened at the National theater in Los Angeles[10] on October 31, 1974, and grossed $18,455 in its first weekend, increasing its gross the following weekend with $19,506,[11] with a total gross of $53,000 in two weeks.[10] In two months, Variety tracked it grossing $250,000 from the major markets it covered.[12] The film was successful during its theatrical release in Winnipeg, Manitoba,[13] where it opened on Boxing Day 1974 and played continuously in local cinemas over four months and over one year non-continuously until 1976.[14] The soundtrack album sold 20,000 copies in Winnipeg alone, and was certified Gold in Canada.[13] The film played occasionally in Winnipeg theaters in the 1990s and at the Winnipeg IMAX theater in 2000, drawing a "dedicated audience".[14]

Williams performed the song "The Hell of It" on a 1977 episode of The Brady Bunch Hour, and also performed it in The Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew Meet Dracula the same year.

Critical reception

[edit]Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote that the film attempted to parody "Faust, The Phantom of the Opera, The Picture of Dorian Gray, rock music, the rock music industry, rock music movies and horror movies. The problem is that since all of these things, with the possible exception of Faust (and I'm not really sure about Faust), already contain elements of self-parody, there isn't much that the outside parodist can do to make the parody seem funnier or more absurd than the originals already are."[15] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film two stars out of four, writing that "what's up on the screen is childish; it has meaning only because it points to something else. To put it another way, joking about the rock music scene is treacherous, because the rock music scene itself is a joke."[16] Variety called the film "a very good horror comedy-drama" with "excellent" camera work, and stated that all the principal actors "come across extremely well."[17] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times called the film "delightfully outrageous," adding that De Palma's sense of humor "is often as sophomoric as that which he is ostensibly spoofing. Fortunately, this tendency diminishes as Phantom of the Paradise progresses, with the film and the Faustian rock opera within it gradually converging and finally fusing in a truly stunning and ingenious finale."[18] Pauline Kael of The New Yorker was positive, stating, "Though you may anticipate a plot turn, it's impossible to guess what the next scene will look like or what its rhythm will be. De Palma's timing is sometimes wantonly unpredictable and dampening, but mostly it has a lift to it. You practically get a kinetic charge from the breakneck wit he put into 'Phantom;' it isn't just that the picture has vitality but that one can feel the tremendous kick the director got out of making it."[19] Richard Combs of The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote, "Too broad in its effects and too bloated in style to cut very deeply as a parody of The Phantom of the Opera, Brian De Palma's rock horror movie is closer to the anything goes mode of a Mad magazine lampoon ... Phantom of the Paradise nevertheless offers fair competition to and comes on much like Tommy."[20]

On Rotten Tomatoes the film holds a score of 82% based on 65 reviews, with an average grade of 7.3 out of 10 and the consensus: "Brian De Palma's subversive streak is on full display in Phantom of the Paradise, an ebullient rock opera that rhapsodizes creativity when it isn't seething with disdain for the music industry."[21]

Home media

[edit]On September 4, 2001, Phantom of the Paradise was made available on DVD by 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment.

The film was given a Blu-ray release on August 4, 2014, by Shout! Factory under the Scream Factory label. This edition features an audio commentary, interviews, alternate takes, the original "Swan Song" footage, and original trailers, and television and radio spots.

Awards

[edit]The film was nominated for an Academy Award for Original Song Score and Adaptation[22] and a Golden Globe Award for Best Original Score – Motion Picture.[23]

Legacy

[edit]A fan-organized festival, dubbed Phantompalooza, was held in 2005 in Winnipeg, where the fanbase took particularly strong root.[24] That event featured appearances by Gerrit Graham and William Finley, in the same Winnipeg theatre where the film had its original run in 1975. A second Phantompalooza was staged April 28, 2006, reuniting many of the surviving cast members and featuring a concert by Paul Williams.

A successful concert production of the show, adapted by Weasel War Dance Productions, premiered March 12, 2018, at The Secret Loft in New York City.[25]

Musician Sébastien Tellier wrote about his song "Divine" on his album Sexuality: "This is my tribute to the Beach Boys and the Juicy Fruits (from the 1974 musical Phantom of the Paradise). It's about a time of innocence – when having fun was more important than picking up girls. I visualise a bunch of kids having fun on the beach and I'd really love to play with them."[26]

According to a Guardian interview with Daft Punk, "Hundreds of bands may tout cinematic references, yet few have them as hard-wired as Daft Punk. Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo and Thomas Bangalter met two decades ago this year, at the perfect cinema-going ages of 13 and 12 ... the one movie which they saw together more than 20 times was Phantom of the Paradise, Brian De Palma's 1974 rock musical, based loosely around Phantom of the Opera (both this and Electroma feature 'a hero with a black leather outfit and a helmet')."[27]

Numerous Japanese artists and authors have designed characters that heavily resemble The Phantom. Some notable examples include Hirohiko Araki's Purple Haze, Kentaro Miura's Femto,[28] Kazuma Kaneko's design for Illuyanka in the Shin Megami Tensei franchise and Digimon's Apocalymon and Beelzemon.

The electrocution scene in Romeo's Distress was created in tribute to Beef's death on stage.

On October 26, 2024, a 50th anniversary screening of the movie was held at the Majestic Theater in Dallas, one of the original filming sites representing the interiors of Swan’s Paradise concert venue. It was followed by a Q&A with Paul Williams.

On November 2, 2024, a 50th anniversary screening of the movie was held at the Burton Cummings Theatre in Winnipeg. It had a Q&A with Paul Williams, and three of the Juicy Fruits.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ https://johnalvinart.com/about-john-alvin/phantom_of_the_paradise-2/

- ^ https://www.swanarchives.org/Promotion.asp

- ^ "Phantom of the Paradise (AA)". British Board of Film Classification. August 9, 1978. Retrieved November 19, 2012.

- ^ Szpirglas, Jeff (November 21, 2011). "Looking back at Brian De Palma's Phantom Of The Paradise". Den of Geek!. Den of Geek.

- ^ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 282. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ https://www.swanarchives.org/Production.asp

- ^ Adams, Sam (May 24, 2012). "Actress, memoirist, and set dresser Sissy Spacek looks back on some key roles". AV Club. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ 'Phantom' Sold to Highest Bidder: Fox Kilday, Gregg. Los Angeles Times 20 July 1974: a7.

- ^ "The Swan Archives - Production". swanarchives.org. 2006. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- ^ a b "'Bears And I' And L.A. $113,400". Variety. November 13, 1974. p. 10.

- ^ "Phantastic!!! (advert)". Variety. November 13, 1974. p. 23.

- ^ Silverman, Syd (May 7, 1975). "Variety Chart Summary For 1974". Variety. p. 133.

- ^ a b Carlson, Doug. "Why Winnipeg? The 1975 Phantom Phenomenon" www.phantomoftheparadise.ca. p. 1. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ a b Carlson, Doug. "Why Winnipeg?". p. 4. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (November 2, 1974). "Film: Brian De Palma's 'Phantom of the Paradise'". The New York Times. 16.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (December 24, 1974). "A pointless 'Phantom' falters too often". Chicago Tribune. p. 17.

- ^ "Phantom of the Paradise". Variety. October 30, 1974.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (November 1, 1974). "'Phantom' with a Rock Twist". The Los Angeles Times. p. IV-1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kael, Pauline (November 11, 1974). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. p. 178.

- ^ Combs, Richard (May 1975). "Phantom of the Paradise". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 42 (496): 113.

- ^ "Phantom of the Paradise". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ "The 47th Academy Awards (1975) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. April 8, 1975. Retrieved November 22, 2018. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. "'Phantom of the Paradise' Song Score by Paul Williams; Adaptation Score by Paul Williams and George Aliceson Tipton". Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ "The 32nd Annual Golden Globe Awards (1974)". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on April 30, 2008. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ Carlson, Doug. "Why Winnipeg?". Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ "Revised And Reconstructed, Brian De Palma's PHANTOM OF THE PARADISE Is In Concert At Underground Venue, The Secret Loft". March 9, 2018. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- ^ "Sebastien Tellier--Sexuality". Recordmakers.com. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2012.

- ^ "Punk Fiction". The Guardian. July 13, 2007. Retrieved May 5, 2012.

- ^ Glenat Manga Editions. "INTERVIEW Le Grande Retour! Berserk". Facebook. Glenat Manga Editions.

External links

[edit]- Phantom of the Paradise at IMDb

- Phantom of the Paradise at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Phantom of the Paradise at the TCM Movie Database

- Detailed article: Why Winnipeg? The 1975 Phantom Phenomenon

- 1974 films

- 1974 comedy horror films

- 1974 independent films

- 1974 musical films

- 1970s American films

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s monster movies

- 1970s musical comedy films

- 1970s satirical films

- 20th Century Fox films

- American comedy horror films

- American independent films

- American monster movies

- American musical comedy films

- American rock musicals

- American satirical films

- English-language comedy horror films

- English-language musical comedy films

- Films about composers

- Films based on multiple works

- Films based on The Phantom of the Opera

- Films based on The Picture of Dorian Gray

- Films directed by Brian De Palma

- Films set in 1974

- Films set in a theatre

- Films set in New York City

- Films shot in Dallas

- Films shot in New York City

- Parodies of horror

- Works based on the Faust legend

- Paul Williams (songwriter) albums

- 1974 science fiction films

- 1974 comedy-drama films

- English-language science fiction horror films

- English-language independent films